Emancipation

One hundred and fifty years ago, on July 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln discussed with his cabinet for the first time the possibility of an emancipation proclamation. Lincoln read out to his colleagues a draft declaring that the slaves in the states (if any) still in rebellion on January 1, 1863, would become and remain free. Many cabinet members were surprised by Lincoln’s proposal and some opposed it. Lincoln shelved the draft, but resurrected it after the Union victory at Antietam, and issued a preliminary proclamation on September 22, 1862, and followed up with a final proclamation on January 1.

One hundred and fifty years ago, on July 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln discussed with his cabinet for the first time the possibility of an emancipation proclamation. Lincoln read out to his colleagues a draft declaring that the slaves in the states (if any) still in rebellion on January 1, 1863, would become and remain free. Many cabinet members were surprised by Lincoln’s proposal and some opposed it. Lincoln shelved the draft, but resurrected it after the Union victory at Antietam, and issued a preliminary proclamation on September 22, 1862, and followed up with a final proclamation on January 1.

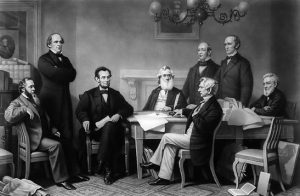

The July 22 cabinet meeting is one of the most famous and familiar in American history, in part because Francis Carpenter’s wonderful painting of the event, copied above. Surely, one would think, nothing new can be said about such a well-researched and well-documented event. Not so.

It is often said, for example, that two members of the cabinet were not surprised by Lincoln’s draft: Secretary of State William Henry Seward and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. According to Welles, Lincoln had discussed the idea of an emancipation proclamation with Seward and Welles ten days earlier, during a carriage ride to a funeral in Georgetown.

This statement by Welles, although it appears in the book we now know as the Welles Diary, was clearly not written in 1862. The tone and tense show that this part of the book was written years later. Moreover, there was a fourth person in the carriage that day: Seward’s daughter-in-law Anna, and it seems unlikely that Lincoln would raise such a sensitive subject in her presence. Welles mentioned the carriage ride in a letter to his son on the same day, but did not mention emancipation, or indeed that anything important was discussed. It seems, in short, that the “carriage ride conversation” was a later invention by Welles: he and Seward were probably just as surprised as the others by Lincoln’s draft.

It is also often said that, at the July cabinet meeting, Seward favored the idea of a proclamation but opposed only its timing. “I approve of the proclamation,” Seward reportedly said, “but I question the expediency of its issue at this juncture. . . . It may be viewed as the last measure of an exhausted government . . . our last shriek on the retreat.” Seward advised Lincoln to “give it to the country supported by military success.”

These quotes are from an 1866 book by Carpenter, the artist, who said that he heard them from Lincoln himself. Perhaps: but the language is suspiciously similar to that attributed to Seward in an 1864 article in the Cincnnati Daily Gazette. And much other evidence, including notes take at the time by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, suggests that Seward did not support the proclamation at all: he opposed the proclamation and also questioned the timing. Seward feared that an emancipation proclamation would lead the southern slaves to rise up against their masters, with dreadful consequences. He also worried that a proclamation would lead the European nations to recognize the South.

Many accounts imply that, by the end of the July 22 meeting, there was a consensus: the proclamation would issue as soon as there was a major military victory. But if Seward, Lincoln’s closest adviser, opposed the proclamation so strenuously, there was no such consensus by the end of the meeting. The fate of the proclamation, and millions of men and women, would depend not merely on a battle, but on Lincoln and his cabinet and their further debates.

My book will explain these points in more detail, but they remind us that history can never be definitive, that it is by its nature iterative. We know more about Lincoln and his cabinet today than we did fifty years ago, both because of the discovery of new sources and new interpretations of old sources. In another fifty years, however, today’s books will look dated. I believe historians will have new tools: that essentially all nineteenth century newspapers will be available in digital form; that one will be able to search these newspapers in more powerful ways; that one will be able to digitize illegible manuscripts using new software; and then use software to skim these digital manuscripts for new or surprising information. In short, even if no new sources are discovered, we will be able to make much better use of existing sources, and they will shed new light on events.

Stanton is said to have said, upon Lincoln’s death, that he “belongs to the ages,” and that means ages yet to come.