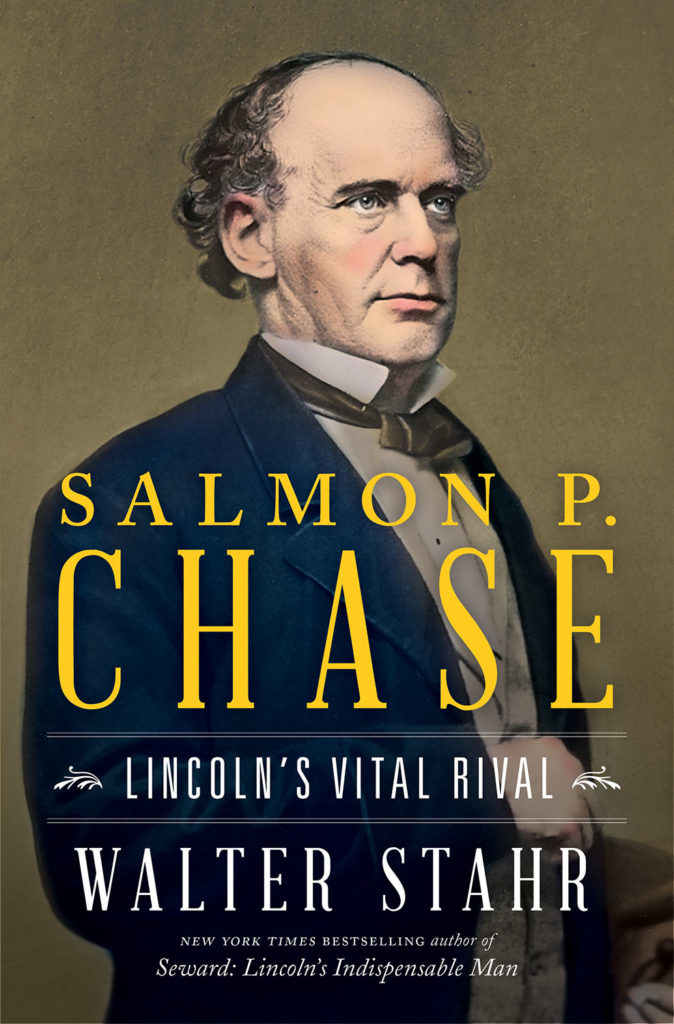

Salmon P. Chase

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, Bookshop, IndieBound

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, Bookshop, IndieBoundTitle: Salmon P. Chase

Published by: Simon & Schuster

Release Date: November 9, 2021

Pages: 832

ISBN13: 978-1501199233

Overview

Salmon P. Chase is best remembered as a rival of Lincoln’s for the Republican nomination in 1860—but there would not have been a national Republican Party, and Lincoln could not have won the presidency, were it not for the vital groundwork Chase laid over the previous two decades. Starting in the early 1840s, long before Lincoln was speaking out against slavery, Chase was forming and leading antislavery parties. He represented fugitive slaves so often in his law practice that he was known as the attorney general for runaway negroes. He strengthened his national reputation, as a progressive and an antislavery leader, first as federal senator (from 1849 through 1855) and then as Ohio’s governor (from 1856 through early 1861).

Tapped during the secession winter by Lincoln to become Secretary of the Treasury, Chase would soon prove vital to the Civil War effort, raising the billions of dollars that allowed the Union to win the war, while also pressing the president to emancipate the country’s slaves and recognize black rights. When Lincoln had the chance to appoint a chief justice in late 1864, he chose his faithful rival, because he was sure Chase would make the right decisions on the difficult racial, political, and economic issues the Supreme Court would confront during Reconstruction.

Drawing on previously overlooked sources, this book sheds new light on a complex and fascinating political figure, as well as on the pivotal events in the years before, during and right after the Civil War. Salmon P. Chase tells the story of a man at the center of the fight for racial justice in 19th century America.

Praise

“Long viewed as either a pretentious thorn in Lincoln’s side, or the beneficiary of Lincoln’s generosity in overlooking his flaws for the good of the nation, Salmon P. Chase has long deserved a full, fresh, fair reappraisal. With this sweeping, meticulously researched, and convincingly argued biography, Walter Stahr has produced just such a study. Stahr adds dimension and depth to Chase’s image and restores him to his rightful place as a genuine antislavery hero, however flawed by clumsy ambition. Anyone interested in the freedom politics of the mid-19th century should regard this fine book as an essential resource.”

—Harold Holzer, winner of the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

“With meticulous research, Walter Stahr breathes new life into Salmon Chase, friend and rival of Lincoln, senator, governor, finance secretary and chief justice. Above all, this is a book about racial justice: about Chase’s long quest to end slavery and secure Black rights in America.”

—Brad Meltzer, New York Times bestselling author of The Lincoln Conspiracy

Backstory

When I started to think about my fourth book, I offered several suggestions to my editor at Simon & Schuster, the late Alice Mayhew, before we settled on Salmon P. Chase. I was not initially enthused about Chase: like many Lincoln lovers, I viewed him as ambitious, self-centered, even somewhat devious at times. Alice, an even more ardent Lincoln lover, agreed; but she also believed that Chase needed and deserved a new biography. We agreed on terms, and I plunged into the letters, diaries and speeches of Salmon P. Chase.

My research was made both easier and harder because I now live, not merely part-time but full-time, in southern California. On the plus side, I had a great “local library” at the University of California, Irvine, whose staff helped me borrow books and microfilms from other libraries. A little farther afield, I spent many happy days working at the A.K. Smiley Public Library in Redlands, California. The Smiley collection includes the paper copies of the Chase letters assembled and microfilmed by one of my predecessors, John Niven; approximately fifty thousand pages of paper. I did not turn every page, but I turned and read thousands of pages. I also spent many happy days at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. The Huntington has some original letters to/from/about Chase, and also has a copy of the Niven microfilm. If there were a prize for most days in the Huntington microfilm room, I would win the prize.

I also did some research at other facilities: the Library of Congress in Washington, the Ohio History Center in Columbus, the Cincinnati Museum Center and Cincinnati Public Library and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, to name a few. I was so fortunate that the Library of Congress had placed its collection of Chase papers “online,” so that I could look at those from the comfort of home, rather than the reading room there. And I hired research assistants, in various places, to undertake various tasks, including just reading some of Chase’s horrible handwriting.

I found some sources that prior biographers did not find. For example, the book starts with a speech that Chase gave to a large black audience in Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1865. Prior books mention this speech, but they reference the version published a year later, in a book by Chase’s friend Whitelaw Reid. I found, and used, a version of the speech that appeared in the papers in May 1865, considerably closer, I think, to what Chase actually SAID on that day.

One of my other key sources was a manifesto that Chase published in 1844, in which he set out what he called the “Liberty Man’s Creed.” Chase boldly declared here his goal: to elect antislavery candidates to state and federal offices so that, within a few years, slavery ended in all the states.

Of course, my research and writing were considerably impeded when libraries closed in early 2020. Smaller, local libraries have re-opened, but the large research libraries (the Huntington) have remained closed for more than a year. I have had to work from the notes that I took before the libraries closed, with copies provided by some kind library staff members, and with copies obtained in a few cases by research assistants.