John Jay

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, Bookshop, IndieBound

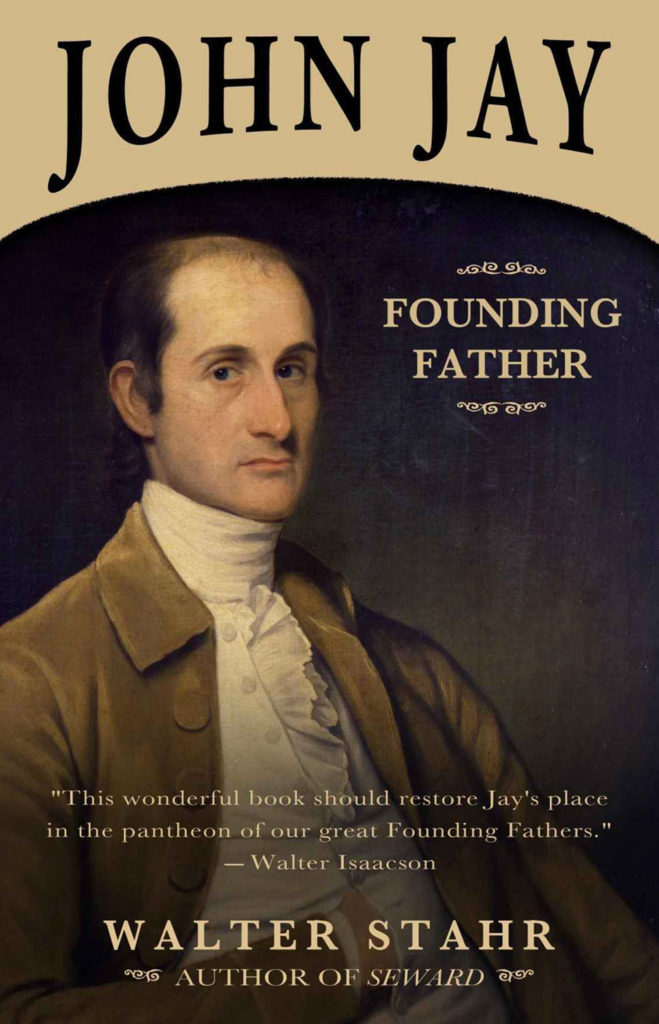

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, Bookshop, IndieBoundTitle: John Jay: Founding Father

Published by: Diversion Publishing

Release Date: August 22, 2017

Pages: 512

ISBN13: 978-1635763362

Overview

Most people have heard John Jay’s name but they do not know much about him. If they know anything, they know that he was one of the authors of the Federalist Papers and the man who negotiated Jay’s Treaty.

Jay was indeed an author of the Federalist Papers and the negotiator of the treaty which bears his name, but he was much more. He was a delegate to the first Continental Congress in 1774, principal author of the first New York state constitution, Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court, President of the Continental Congress, America’s representative abroad in Madrid and Paris, negotiator of the treaty that ended the Revolutionary War, secretary for foreign affairs during the years just before and after the Constitutional Convention, ardent and effective advocate of the Constitution, first Chief Justice of the United States, and finally governor of New York from 1795 through 1801.

Jay was the trusted friend and colleague of other American leaders: Washington, Franklin, Adams and Hamilton. Washington knew that Jay had the “talents, knowledge and integrity which are so necessary” to serve as the nation’s first Chief Justice. Adams believed that, in the process of developing and adopting the Constitution, Jay was “of more importance than the rest, indeed of almost as much weight as the rest.”

John Jay: Founding Father tells the story of Jay’s life from his birth in 1745 to his death in 1829. It deals not just with his work but also with his personal life: his wife, the lively and intelligent Sarah Livingston Jay, and his friends, such as Robert Livingston, who later in life became his political enemy. The book, in short, aims to bring to life for a new generation one of the greatest Americans of his generation.

Praise

“Stahr has succeeded splendidly in his aim of recovering the reputation of John Jay as a major founder. His biography is a reliable and clearly written account [and] makes a persuasive case for including Jay among the first rank of Revolutionary leaders.”

—Gordon S. Wood in The New York Review of Books

“Walter Stahr's even-handed account, the first big biography of Jay in decades, is riveting on the matter of negotiating tactics, as practiced by Adams, Jay and Franklin.”

—The Economist

“Stahr’s Jay is a welcome and worthy biography.”

—The Sunday Times (London)

“Walter Stahr, an independent scholar, has written a fascinating, learned and beautifully written biography of a major figure of the American Revolution, one who has been too long overlooked. Mr. Stahr deserves consideration for the Pulitzer Prize for biography.”

—Washington Times

“Mr. Stahr is a superlative biographer, reporting the criticisms made of his subject and then showing why, in most cases, Jay knew better than his contemporary critics or later historians.”

—New York Sun

“Until Walter Stahr's splendid new biography appeared, the most recent biography of Jay was Frank Monaghan's John Jay: Defender of Liberty against Kings and Peoples (1935), published some seven decades ago.”

—Journal of American History

“Walter Stahr's excellent new biography should re-establish Jay's standing as one of America's great statesmen. It portrays Jay's life with a balance and command of the material worthy of the subject.”

—Weekly Standard

“Stahr . . . captures both his subject's seriousness and his thoughtful, affectionate side as son, husband, father and friend. In humanizing Jay, Stahr makes him an appealing figure accessible to a large readership and places Jay once again in the company of America's greatest statesmen, where he unquestionably belongs.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Walter Stahr has not only given us a meticulous study of the life of John Jay, but one very much written in the spirit of the man. It is thorough, fair, consistently intelligent, and presented with the most scrupulous accuracy.”

—Ron Chernow, author of Alexander Hamilton

“Walter Stahr writes with great insight, and this wonderful book should restore Jay’s place in the pantheon of our great Founding Fathers.”

—Walter Isaacson, author of Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

Backstory

For four years in the late 1990s, my wife, children and I lived in Hong Kong. I was working as an internal lawyer for an American financial firm; our home was a beautiful (but small) apartment on the south side of Hong Kong island, perched high above the South China Sea. From our apartment window we could look down upon the American Club, where my wife played a lot of tennis and my children learned to swim. It was a busy life but a good one.

One evening I was sitting in our apartment, reading a book about the American Civil War. What happened next is best related as dialogue, although there was no one else in the room at the time.

Stahr: “This book was not very well done; even I could have done better.”

Voice: “If you really think that, Stahr, why don’t you do it?”

Stahr: “Do what?”

Voice: “Write a book on American history.”

Stahr: “Don’t be ridiculous: I do not have the training to do that: I am just a lawyer, not a historian.”

Voice: “Don’t be ridiculous: you have taken lots of history courses, done research in the Library of Congress, read hundreds of history books, even the footnotes.”

Stahr: “But I don’t have time: I have a full-time job and I travel a lot.”

Voice: “What better time to do some preliminary reading than while you travel?”

Stahr: “OK, let me think about a possible topic.”

I remember at least two topics that I considered in the weeks which followed. One was Civil War prisons: I was intrigued by the comment in James McPherson’s book Battle Cry of Freedom that “Civil War prisons and the prisoner exchange question badly need a modern historian.” Another was Gouverneur Morris: I noticed a similar comment about Morris in a footnote in Richard Bernstein’s great book Are We to Be a Nation?

I started reading about Morris, a fascinating figure, author of the immortal words “We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union.” I decided that one easy thing to read would be biographies of some of Morris’s best friends: Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and Robert Livingston.

Libraries were just starting to put their catalogs online, and I used these catalogs to look for a biography of Jay. The most recent full-length book I could find was Frank Monaghan’s biography from 1935. Using on online used-book service, also just getting started at this time, I bought a used copy of Monaghan’s book. As I read, there was another bit of dialogue.

Stahr: “Monaghan’s book on Jay is not very good; even I could do better.”

Voice: “Then why don’t you research and write a biography of Jay?”

Stahr: “But what about Gouverneur Morris?”

Voice: “Look, Morris is colorful, with his romantic affairs and his wooden leg, but he is not anywhere near as important as Jay. Jay needs a biography and you could write it.”

Stahr: “OK, I will try.”

By the time we returned from Hong Kong to the United States, at the very end of 1998, I had decided to attempt a life of Jay. My plan was that I would take a year off, do all the research, and then do the writing while working in some kind of legal job in Washington. I did not have an agent or a publisher, but I thought I could sort out those details later.

“Man plans, God laughs.” Two things happened to my plan. First, it became clear that a year would not suffice for the research on Jay; it was going to take a long time to read and digest all the material I was finding. Second, Emerging Markets Partnership, a private equity firm based in Washington, was interested in hiring me to work on their Asian legal issues. I started work with EMP in March 1999, resolved to keep reading about Jay on nights and weekends.

A few years later, perhaps it was 2003, I told the senior people at EMP Global that I needed more time to research and write, that I was thinking of resigning and leaving the firm. Instead we worked out a part-time arrangement, allowing me to work one week for EMP and then one week on Jay. I will be forever grateful to EMP for its flexibility, for this gave me the time to do the research, especially in New York City, and also gave me the legal work I needed to pay the bills. My part-time status lasted for about one year, but by the end of that time I was more or less done with research outside of Washington.